Re-Awokening

Lauryn Mwale describes how black lives matter protests during a pandemic reshaped her views on race

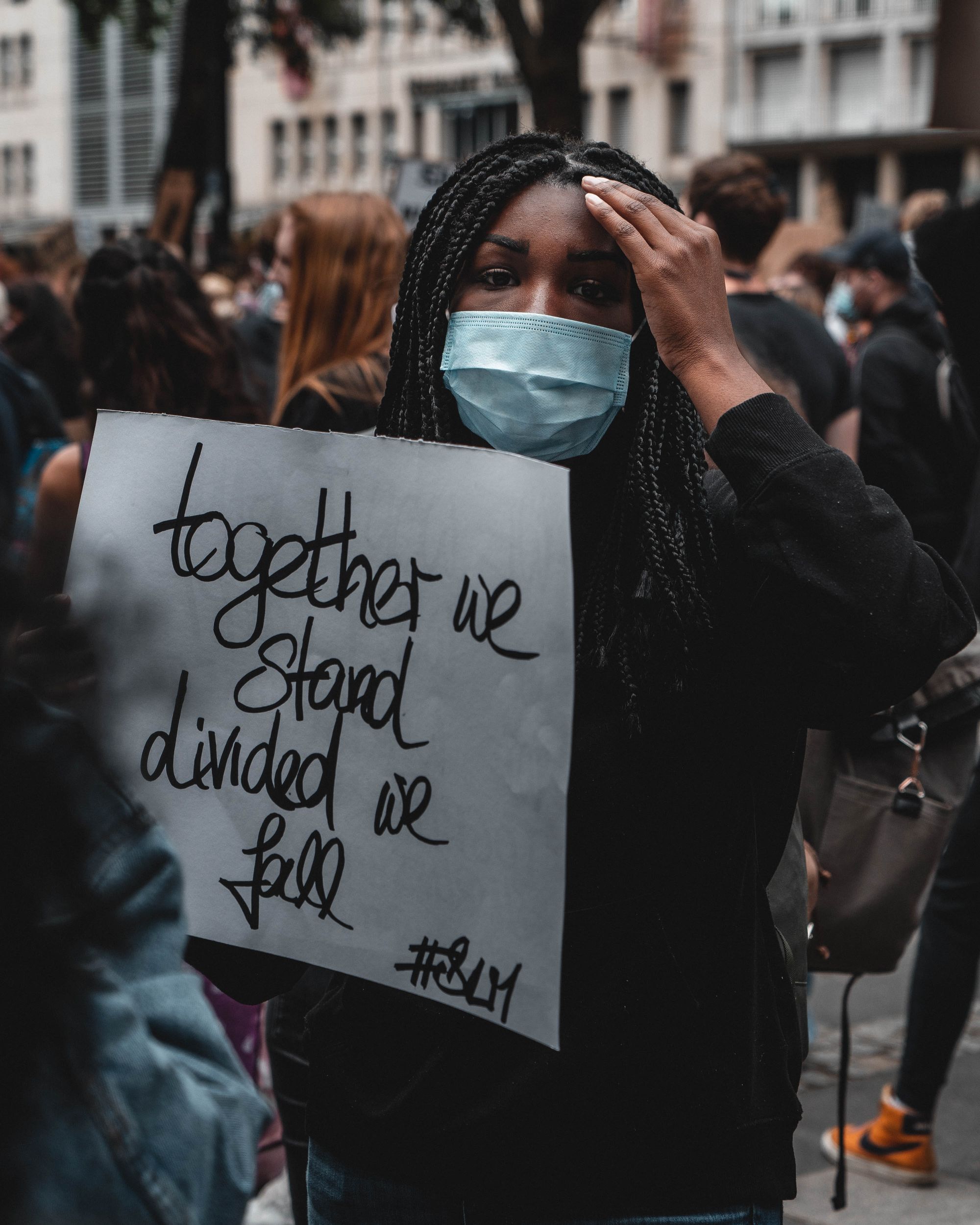

In 2020, something in the world shifted when an American policeman, Derek Chauvin, knelt on George Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and forty-six seconds. This is not the first time a black man died at the hands of a white policeman. Maybe it got the attention it did because it happened during the coronavirus pandemic, a time when many people were trapped at home needing something to do.

I realised my blackness for the first time as an eighteen year old wandering the streets of Edinburgh

It was a beautiful thing to see the world wake up. Protests and rallies, virtual activism and anti-racism books soaring to the top of Amazon’s bestsellers lists. People risked their health to march in cities across the world. When I finally joined the throng, I was moved to tears. Afterwards, I had a socially distanced walk with a friend who I hadn’t seen for months. We sat down, a safe seven-feet apart, and laughed about the witty signs we had seen on display.

As a Zambian who lives in Scotland, I realised my blackness for the first time as an eighteen year old wandering the streets of Edinburgh, noticing that no one looked like me. I sat in lecture theatres and walked crowded halls, the only black face in the crowd. Yet, I didn’t claim the Black Lives Matter movement as something I had to be a part of. Needless to say, I believe in the value and validity of black lives but always felt better placed to speak of the social and economic trauma of colonialism, a history I carry in my blood by virtue of my birthplace. I felt better placed to have weary, angry debates about the fallacies of African governments, and even though I listened eagerly to Black British and African-American histories, they felt separate from me. Then George Floyd died and I understood collective black trauma.

What are we doing to dismantle systems that negatively impact vulnerable individuals?

I thought back to a myriad uncomfortable moments and upsetting comments. The intense feelings of shame, embarrassment and anger that conversations with my white friends prompted. I thought about all the times I had diplomatically responded to their “Africa” questions. I remembered those who messaged me to check-in during the 2017 political unrest in Zimbabwe, forcing me to explain I am Zambian when they responded with quizzical emojis. At first, I thought they were being sweet. But when the same person offered condolences a third time, I recognised the situation for what it was: Her need to perform woke whiteness meant more than the specifics of my identity.

I’ve had the good fortune to spend lockdown in place and I finally read Reni Edo-Lodge’s incredible book Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race, an incredible book that expounds on the particulars of Black British history in cities like Birmingham and Bristol, using biting humour. Her book gave me permission to stop coddling those that weren’t as bad as the right-wing extremists but just as complicit in perpetrating racism.

Throughout history, and even during this pandemic, black men, women and children have met untimely deaths for no reason other than their skin colour. We are more likely to die from coronavirus in the United Kingdom. Many keep talking about the new normal but 2021 has shown that there is a lot that 2020 and its traumas didn’t disappear at midnight, which begs the question: what are we doing to dismantle systems that negatively impact vulnerable individuals?