Learning, Anew

Lecturer and doctoral candidate Thulile Khanyile reflects on how the pandemic has affected her work as a teacher and researcher, and learning in higher education.

The urgent need for greater knowledge and value creation in Africa

Suddenly, I couldn’t see the nods, neither could I bear witness to the confused and often indifferent faces of students.

Academia where knowledge transfer, knowledge and value creation formally occur; like many sectors was affected and challenged to respond with speed to the COVID-19 global pandemic. Knowledge transfer in the form of course work predominantly at undergraduate level was migrated to online platforms. As a lecturer to undergraduate second year medical students, Master of Medicine (MMed) clinicians specialising in haematology/pathology and second year biomedical engineering students; this would also affect me. I too would have to adapt to online knowledge transfer delivery platforms. Although I had made use of the zoom platform before, I didn’t imagine it would be different when delivering my first virtual lecture.

I’m generally comfortable with public speaking and the arty side of me comes alive in the presence of an audience. Naturally, I thought I would be okay until I couldn’t see my audience of students. I realised just how much seeing my students enabled me to deliver my content more meaningfully. Suddenly, I couldn’t see the nods, neither could I bear witness to the confused and often indifferent faces of students. The mute function is as advantageous as it is a disadvantage. I don’t want to hear my students have side conversations, but I do want to hear the odd “I don’t understand” which often rolls off the tongue albeit unintentionally. Physical lectures with especially this group, had always been conversational as they are qualified medical doctors from which I too, learn a great deal from. With this specific group the zoom platform sucked the fun out of it for me.

The platform of choice for undergraduate students was a university internal teaching and learning platform. This meant recording the PowerPoint based content as videos and uploading them onto the platform ahead of the lecture period for students to upload, watch at their own time, and send queries to an online forum/chat portal for further correspondence. I enjoy doing the voice overs for this content (the arty side of me again I suppose), but other than that I think students, particularly undergraduates, should always have the option to attend physical lectures. This exercise requires tons of data to enable students to gain the knowledge. Telecommunication companies had to be a major part of this response by contributing to the provision of data. To be fair this contribution is late. Data should be free to all registered students on the continent regardless of the presence or absence of a pandemic.

Beyond COVID-19 we could continue like this and we may all become used to it as the “norm”, but something must be said about students possessing varying characteristics, personalities and learning modalities. Physical interaction still provide immense benefit for some students and a balance must be struck to cater for all learning needs beyond the adoption of technology. The component of higher education that is not only about books, is the cultural experience of university life, and all the social, networking and development of interpersonal skills. The challenges and concerns around time spent with people through digital devices versus physically interacting with people have been highlighted and as the education system, we don’t want to exacerbate them.

As we consider the most effective operational model for knowledge transfer, we don’t have the luxury of ignoring the social challenges most of our students faced during lockdown restriction periods in the “comfort” of their own homes. This is beyond the obvious resource challenge to which according to a survey conducted by a crowd funding platform called Feenix, “only six percent of students said they have everything they needed to access all the resources they needed at education”. With university residences and off-campus private student accommodations also responding to lockdown restrictions, a large percentage of our students found themselves back in their resource limited and socially challenged homes. Environments that, in some cases, required them to be more than just students. Some were required to be breadwinners and caregivers, using student grants and bursaries as a resource.

Data should be free to all registered students on the continent regardless of the presence or absence of a pandemic.

Despite online knowledge transfer platforms, the residence structure must continue to support our students from the social settings which are not conducive to their advancement. The girl child and women in the home setting has domestic responsibilities, which takes away from their knowledge consuming time and process. Online knowledge transfer platforms are effective and must continue beyond the pandemic. However, if administered in ways that do not consider these and many other circumstances, the most marginalised and resource starved of our students, particularly girls and young women, may realise even less career advancement than we currently observe. Student grants and bursary schemes may very well think online platforms open opportunities for them to fund less in value (money) for the purpose of funding more in quantity (students), but I caution against this line of thinking. The individual needs of students must continue to be catered for adequately.

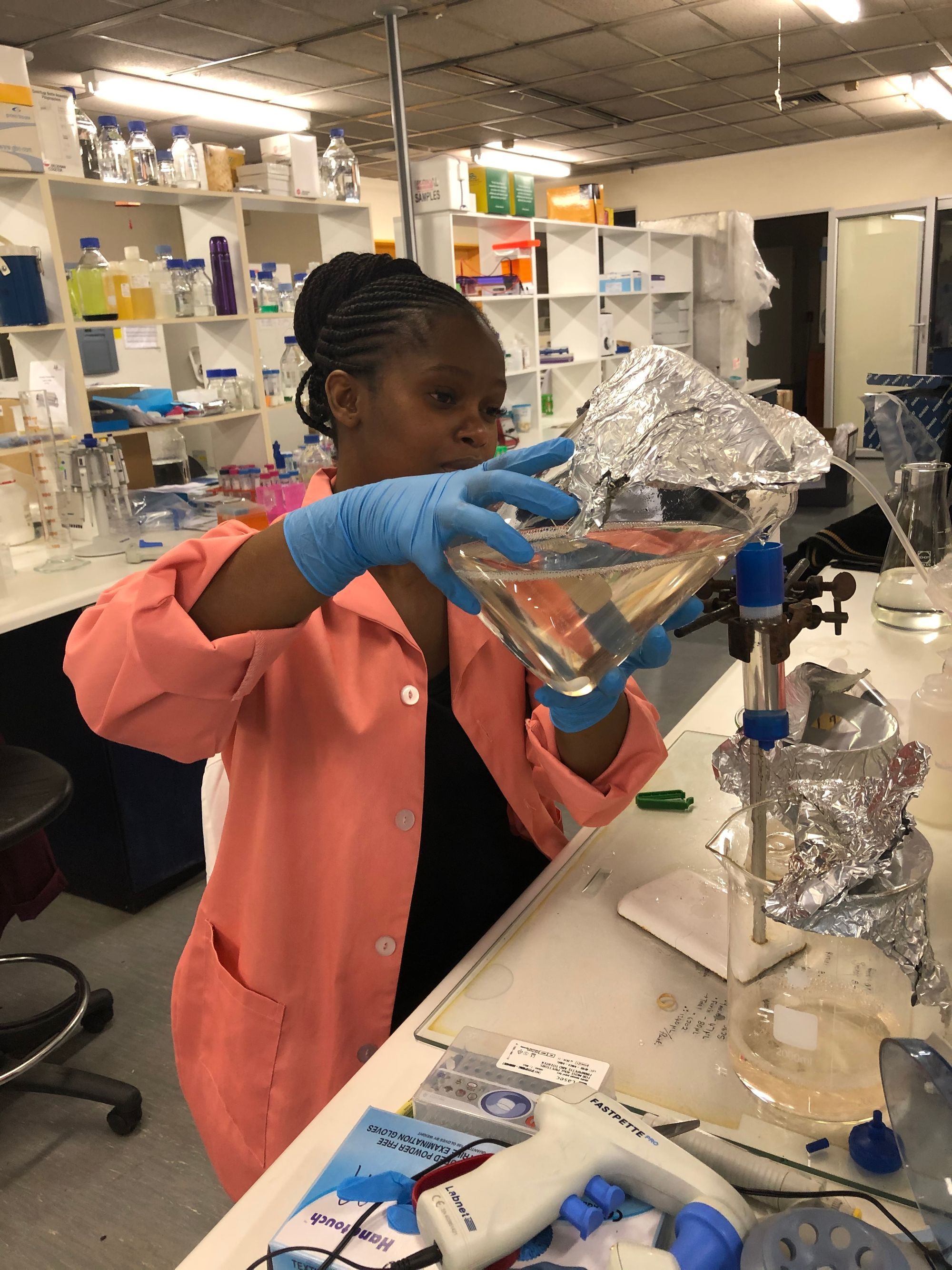

Post-graduate students studying towards masters and doctoral qualifications have a defined mandate. Their role is to solve and/or understand a specified problem by collecting data, drawing conclusions from that data to prove and realise their hypothesis or proposed solution to said problem. These students and researchers (knowledge generators) who COVID-19 lockdown restrictions found in the middle of data collection stage, were stopped dead in their tracks. I experienced this as my doctoral studies have been delayed as I couldn’t continue with my experiments during this time. Working on experimental research where data collection is reliant on biological systems such as mammalian cells that require continuous care and monitoring, meant that I had to halt their growth and re-start it again after hard lockdown.

Empirical sciences such as that done by myself, which predominantly involve experimental-based data collection, from where I am sitting will continue to require the laboratory setting. Ofcourse, as technology develops, we may very well see more simulations and trouble-shooting being carried out virtually to a point where the most adequate experimental conditions are realised ahead of physically conducting the experiments in a lab setting.

Knowledge as it is acquired in the education system from early childhood development up to doctoral level, and its mandate, needs an intervention. In the early stages of my career as an intern at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, I was fortunate to be exposed to the translational part of research and development. Working in a team that was developing a diagnostic tool for tuberculosis and subsequently the commercialisation of the diagnostic made me aware of the deficit in a value creation mindset within the education system. It was only at that point that I began to think about how academia is underutilised for value creation and how its’ mandate does not speak to our current challenges of job creation and poverty alleviation.

There are more people looking for employment than those creating employment which is indicative of how successful our institutions are at creating job seekers.

With the rise in the importance of the knowledge economy and the surge of new technologies of digitization, automation and a heavy emphasis on innovation, academia is finding itself needing to transform to align itself adequately. Loosely stated the academy is now also concerned with developing research outcomes and outputs that can be commercialised, and of greater value to the people. This should in turn result in job creation and poverty alleviation. At least in theory that is what the academy seeks to achieve amongst its other objectives. What academia does well, is create job seekers which the COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted as a significant challenge.

There are more people looking for employment than those creating employment which is indicative of how successful our institutions are at creating job seekers. The operational model of education and academia responds to generating employees and this needs to change. Academia should foster a way of thinking that yields individuals with the ability to create value even if that value is to create systems and environments that make value creation for economic growth a reality.

With the growing number of challenges facing society, we ought to be more deliberate about developing and priming the mindset of ordinary citizens towards identifying and creating solutions that contribute to the development of the knowledge economy. The risk and what we stand to lose as a society is too high for us to leave to chance the emergence of problem solvers amongst us. We must increase our odds of success and the way to do it is by increasing our starting pool of knowledge economy contributors.

The education system including academia should seek to develop a balance between generating employees and employers. Achieving this balance is possible and a model we can prototype and scale already exist. But that is perhaps a story for a different article.